Estratégias para reduzir o tempo sem compressão na RCP são bem-vindas. Uma delas, não prevista no algoritmo do ACLS, mas bastante interessante, é carregar o desfibrilador cerca de 10 a 20 segundos antes da próxima análise de ritmo. Assim, se o ritmo for chocável, a desfibrilação será feita em um tempo menor.

Mas cuidado: choque apenas os ritmos de FV ou TV sem pulso e tenha segurança que todos estão afastados da vítima da parada cardíaca. Esta estratégia será melhor usada por socorristas e equipes mais experientes.

Leia abaixo a matéria completa, com a dica, disponível em https://www.aliem.com/2016/trick-trade-pre-charge-the-defibrillator/

Trick of the Trade: Pre-Charge the Defibrillator

In cardiac arrest care it is well accepted that time to defibrillation is closely correlated with survival and outcome [1]. There has also been a lot of focus over the years on limiting interruptions in chest compressions during CPR. In fact, this concept has become a major focus of the current AHA Guidelines. Why? Because we know interruptions are bad [2,3]. One particular aspect of CPR that has gotten a lot of attention in this regard is the peri-shock period. It has been well established that longer pre- and peri-shock pauses are independently associated with decreased chance of survival [4,5]. Can we do better to shock sooner and minimize these pauses?

CURRENT ACLS STANDARDS

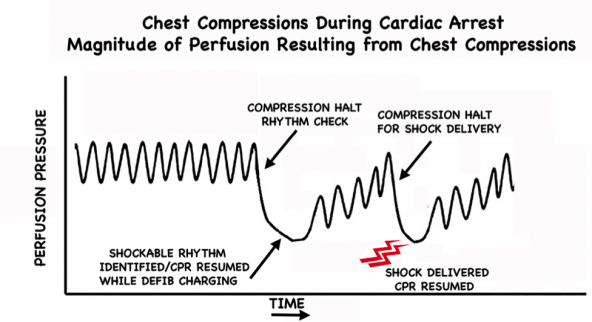

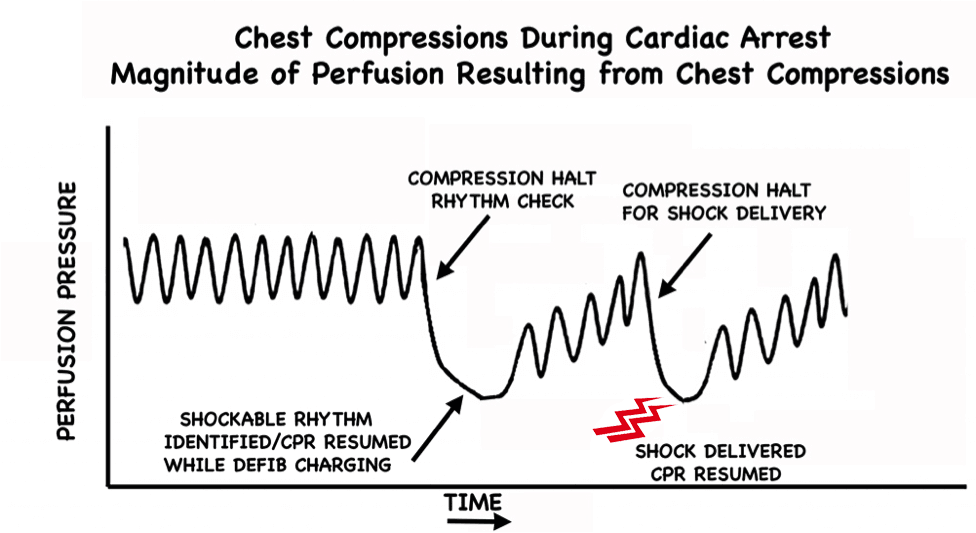

Traditionally during manual CPR when a shockable rhythm is encountered at the rhythm check, providers will charge the uncharged defibrillator at that time. In the meantime, chest compressions are typically resumed while waiting for the defibrillator to charge. Once the defibrillator has finished charging, providers are forced to pause yet again in order to “clear” for shock delivery.

“When a rhythm check by a manual defibrillator reveals VF/VT, the first provider should resume CPR while the second provider charges the defibrillator. Once the defibrillator is charged, CPR is paused to ‘clear’ the patient for shock delivery. After the patient is ‘clear,’ the second provider gives a single shock as quickly as possible to minimize the interruption in chest compressions (‘hands-off interval’).” – 2010 AHA/ACC guidelines

Figure 1: Perfusion pressure changes during CPR without pre-charging the defibrillator. Once a shockable rhythm is identified, there is a delay in shock delivery while awaiting defibrillator charging. There is not just 1 but 2 interruptions in chest compressions. The exact decrease in perfusion pressure during these pauses is variable. Modified from [2].

TRICK OF THE TRADE:

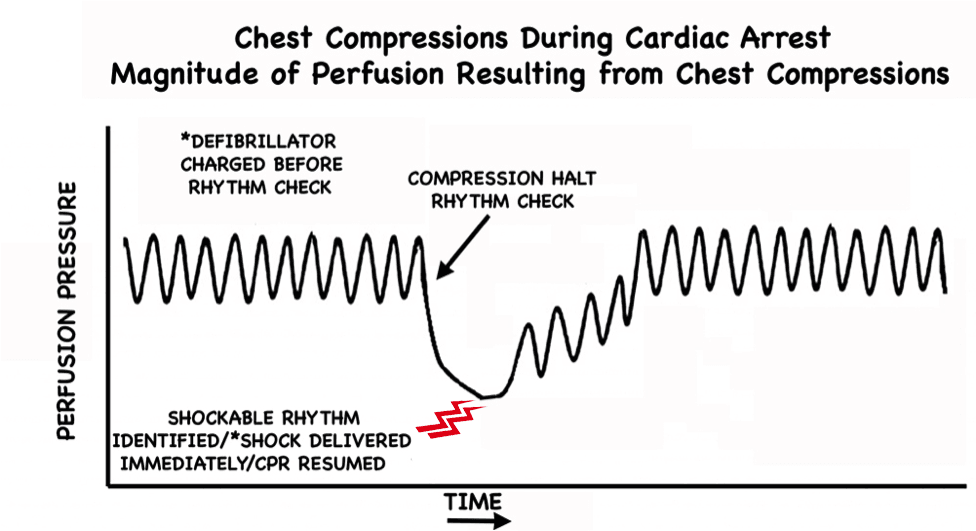

Pre-charge the defibrillator during the active chest compression phase of CPR in anticipation of a shockable rhythm

Why should we wait until a shockable rhythm is encountered at the rhythm check point to charge the defibrillator? This makes little sense. Charging the defibrillator prior to the rhythm check is far more logical. With the defibrillator already charged and ready to go, if a shockable rhythm is encountered at the rhythm check point, the shock can be delivered immediately; and importantly, the second interruption is averted entirely.

Figure 2: Perfusion pressure changes during CPR with pre-charging the defibrillator. Not only is the shock delivered earlier but the second interruption seen in Figure 1 is avoided completely. Modified from [2].

LOGISTICAL TIPS: HOW TO DO THIS

The most important key to ensuring this process runs smoothly lies in preparation and team briefing prior to patient arrival. There must be clear understanding and communication. The timekeeper is tasked with announcing prior to all rhythm checks (15-30 seconds prior is reasonable) that the rhythm check is approaching. Example:

”In 20 seconds we are due for a rhythm check.”

At this point the team member running the defibrillator charges the defibrillator as chest compressions continue uninterrupted until the rhythm check.

With the defibrillator pre-charged, the team is armed and ready to combat a shockable rhythm immediately as it is encountered at the rhythm check.

WHAT IF THE RHYTHM CHECK REVEALS A NON-SHOCKABLE RHYTHM?

If the rhythm check happens to reveal a non-shockable rhythm, CPR can continue as per usual without any alteration. The charge can be manually disarmed, but note that current defibrillators will “hold” the shock for some time (~60 seconds), and if the shock is not delivered in this time frame, the charge will automatically dissipate and require re-charging. (This is why pre-charging should take place within this set time period prior to a rhythm check.) Simply test your particular defibrillator to figure out exactly how long it holds the charge.

WHY IS PRE-CHARGING THE DEFIBRILLATOR NOT IN THE AHA/ACLS GUIDELINES?

The only arguments I have ever heard against the implementation of this strategy is that it may increase the incidence of inappropriate or inadvertent shocks. Presumably, these theoretical concerns have prevented this technique from being recommended as standard practice.

ARE THERE ANY STUDIES ON PRE-CHARGING THE DEFIBRILLATOR?

A multicenter retrospective study was published in 2010 by Edelson et al [6]. Data were gathered from CPR-sensing defibrillator transcripts over a 3-year period. They looked at 680 charge-cycles from 244 cardiac arrests. Charging during compressions correlated with a decrease in median pre-shock pause and total hands-off time in the 30 seconds preceding defibrillation. Interestingly, there was no difference in inappropriate shocks, and there was only one instance of inadvertent shock administration during compressions (which went unnoticed by the compressor).

DISCUSSION

There will likely never be robust data looking at this particular aspect of CPR. Pre-charging the defibrillator is a small thing, but with potentially huge impact. It can be easily taught, easily learned, and is free. I have personally been practicing CPR this way for years now. It has been my experience that it is an incredibly smooth process. All it takes is a little practice and team briefing to ensure all providers are on the same page.

Even with the implementation of other recent techniques that may similarly minimize pauses in chest compressions, such as mechanical CPR and “hands-on defibrillation” (which is of questionable safety), pre-charging the defibrillator still decreases time to defibrillation.

Does it improve outcomes? We may never definitively know. Will it ever make the guidelines? I suspect that eventually it will, perhaps with verbiage similar to something like this:

“It is reasonable to consider pre-charging the defibrillator during chest compressions…”

Until then, it is my opinion that based on early literature, logic, and reasoning, pre-charging the defibrillator in anticipation of a shockable rhythm at the rhythm check is how we should be running our codes.

CONCLUSION

Pre-charging the defibrillator during chest compressions in anticipation of a shockable rhythm at the rhythm check shortens time to defibrillation and minimizes the number of pauses in chest compressions during CPR.

REFERÊNCIAS:

- Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Nichol G, Nallamothu BK, American Heart Association National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Investigators. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest.N Engl J Med. 2008; 358(1):9-17. PMID: 18172170

- Berg RA, Sanders AB, Kern KB, et al. Adverse hemodynamic effects of interrupting chest compressions for rescue breathing during cardiopulmonary resuscitation for ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest. Circulation.2001; 104(20):2465-70. PMID: 11705826

- Cunningham LM et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation for cardiac arrest: the importance of uninterrupted chest compressions in cardiac arrest resuscitation. Am J Emerg Med 2012; 30 (8): 1630 – 8. PMID: 2263371.Clement RA. An extension of Helmholtz’s explanation of Listing’s law. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1990; 10(4):373-80. PMID: 2263371

- Brouwer TF, Walker RG, Chapman FW, Koster RW. Association Between Chest Compression Interruptions and Clinical Outcomes of Ventricular Fibrillation Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Circulation. 2015; 132(11):1030-7. PMID: 26253757

- Cheskes S, Schmicker RH, Christenson J, et al. Perishock pause: an independent predictor of survival from out-of-hospital shockable cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2011; 124(1):58-66. PMID: 21690495

- Edelson DP, Robertson-Dick BJ, Yuen TC, et al. Safety and efficacy of defibrillator charging during ongoing chest compressions: a multi-center study. Resuscitation. 2010; 81(11):1521-6. PMID: 20807672